Geological and Prehistoric Foundations of Arctic Geopolitics

A polar-centric view of the northern hemisphere reveals the Arctic’s inherent and enduring geographic centrality, of increasing geopolitical salience as the polar-thaw continues. Photo: Malte Humpert

The Arctic Institute Planetary Series 2025

To fully understand contemporary Arctic geopolitics and its significance to world politics, it is essential to understand the geopolitical connections interlinking the Arctic region to the rest-of-the-world. This interlinkage has a geospatial-dimension that extends beyond the Arctic due to the region’s increasing global influence (resulting from both climate change and globalization) as well as a temporal-dimension. The geospatial-dimension is well understood today, thanks to Arctic climate researchers and their important work informing the world of the Arctic/global climate nexus. Less well understood is the temporal-dimension, usually framed by a narrow snapshot of modern historical time in which climate change has become paramount. But a longer time horizon challenges us to rethink what ‘Arctic’ means, with multiple cycles of warming and cooling of global significance. These temporal, planetary-scale dynamics can be illustrative for contextualizing Arctic geopolitics and informing long-term planning for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Arctic geopolitics is often contextualized by more recent snapshots of historic-time – whether 20th century, such as the Cold War (1945-90) and World War II (1933-45), or as “far back” as the late 19th century, such as the 1867 Alaska Purchase that made the USA an Arctic state or the colonial Fur Empires (16th-19th century) when the Arctic was first integrated with the modernizing global economic system. These eras are, comparatively speaking, relatively recent in the human story, and in the modernization of the world. This article will instead look back deeper in time – almost a billion years, or Giga-annum; by integrating geological, prehistoric and historic-time will help us understand the remarkable endurance of Arctic globalism (before humanity’s rise) and globalization (after human-time commences in prehistory) across the ages, it will foster a more expansive understanding of the interplay of geology, climate, biology and later humanity with the Arctic across the eons.

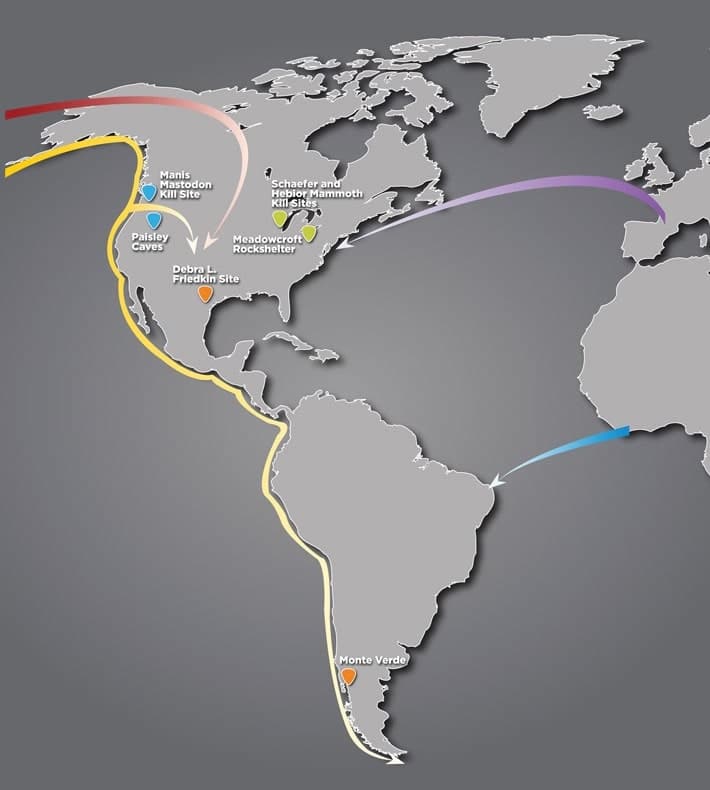

We’ll start our journey during the Cryogenian Period (720-635 million years ago), from Greek kryos (cold) and genesis (birth), of the Precambrian Age, when early life evolved and thrived, showing how the Arctic region and/or Arctic geophysical conditions have had planetary-scale influences across a vast stretch of time that dwarves human-time by many orders of magnitude. The Cryogenian Period is also known as “Snowball Earth,” a 100 million plus years when Earth’s traditionally “polar” cryosphere experienced a global expansion that ultimately entombed our entire planet in ice, after which multicellular life proliferated on Earth, part of the Precambrian’s age of early life. We next leap forward to the (relatively recent) Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) when much of Earth was covered by glaciers, during the Late or Upper Pleistocene Epoch some 29,000-12,000 years ago, when migrating humans found their way to and/or through the Arctic in quest of new hunting and/or fishing territories. Their routes were likely varied – the most popular, and first to gain wide acceptance, by foot along the coastal lowlands of the Bering Land Bridge traversing Beringia.

But archaeologists, finding evidence (in the form fossilized of human footprints) of an earlier arrival, postulate a more northeasterly and earlier-accessible Mammoth Steppe route through what is now northern Alaska, Yukon and southwestern NWT; and/or a Pacific maritime crossing (along what is called the “Fertile Shore,” “Kelp Highway,” or more simply “Coastal” route) adjacent to Beringia, and accessible both before the Bering Land Bridge opened (an opening lasting some 5,000 years) and after it was inevitably flooded by melting glaciers after the LGM concluded some 13,000-11,000 years ago. More controversial and with less scientific evidence is the “Solutrean Hypothesis” across the North Atlantic’s “Icy Crescent” from Europe, a largely hypothetical, alternative prehistoric Atlantic maritime crossing that would again, many millennia later, transport seafaring medieval Vikings to North America.

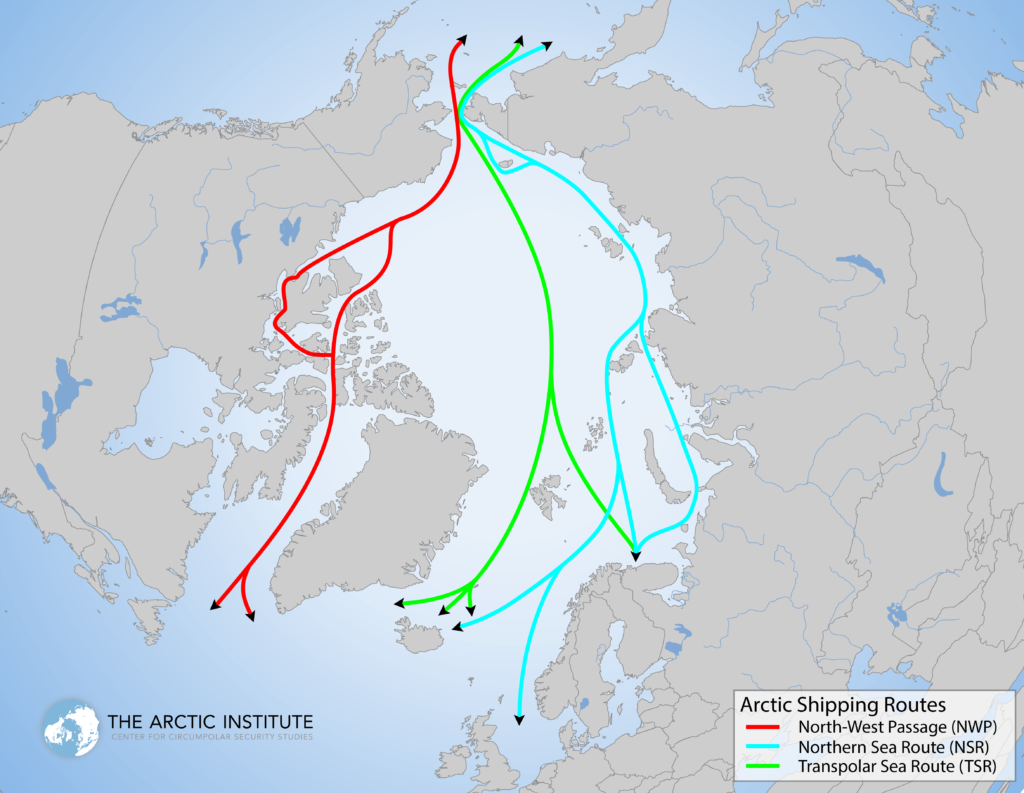

Whether by land through Beringia or along the more northern Mammoth Steppe, or by sea across the Pacific’s Kelp Highway (along the Fertile Coast) or the Atlantic’s Icy Crescent, this multiplicity of migration routes and its extended waves of human migration had profound impacts on the Americas, which had as yet remained unpeopled.1)Dan O’Neill, The Last Giant of Beringia: The Mystery of the Bering Land Bridge (New York: Basic Books, 2004); Robert D. Morritt, Beringia: Archaic Migrations into North America (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011); and Jennifer Raff, Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas (New York: Twelve Books, 2022). Though prehistoric, the geopolitical consequences of this dynamic utilization of the Arctic as a strategic pivot through which humanity flowed, were profound – and indicative of the future geopolitical significance of the Arctic, as exemplified by the diversity of emergent maritime trade routes through the Arctic in the warming Arctic of our own time.2)Malte Humpert, “The Future of the Northern Sea Route – A ‘Golden Waterway’ or a Niche Trade Route,” The Arctic Institute, September 15, 2011, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/future-northern-sea-route-golden-waterway-niche/.

Snowball Earth and the Ice-Age Migrations: Ages of Ancient Arctic Globalism

Indeed, geological and prehistoric deep-history provide us with some compelling metaphors for understanding the Arctic, its place in our planetary history, and its place in the human story. “Snowball Earth” is believed to have been essential to kick-starting evolution beyond microorganisms by toughening up early life forms through shell formation and other adaptations to the era’s planet-wide deep-freeze; the Paleocene/Eocene boundary (where these two epochs transition, around 56 million years ago), when tropical forests colonized the High Arctic, forming what is now a somewhat counterintuitive oasis of “tropical” life that stretches the imaginations of those who perceive the Arctic as perpetually frozen; and the period that followed the LGM, a relatively recent 20,000 odd years ago, when sea levels dropped, revealing the Beringian land bridge connecting Eurasia to North America – one of the principal, but no longer considered only migration routes for the peopling of the Americas.

Near the end of the Proterozoic Eon, which ran from 2.5 billion years ago to around 500 million years ago, Earth had an ice-age like no other during Snowball Earth. While not everyone agrees on the details, most agree all or nearly all of Earth became frozen over, and this frigid period is aptly called the Cryogenic. The theory is there was so much oxygen replacing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that temperatures dropped to freezing even at the equator – with an echo of today’s climate change (but whose direction is in reverse).3)Gabrielle Walker, Snowball Earth: The Story of a Maverick Scientist and His Theory of the Global Catastrophe That Spawned Life As We Know It (New York: Crown Publishers, 2003; and Colin P. Summerhayes, Paleoclimatology: From Snowball Earth to the Anthropocene (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020). It was in essence the opposite of today’s excess atmospheric carbon warming Earth. Some believe the challenge of surviving Snowball Earth toughened life up, hence its notion of “kick-starting” evolution, in new, robust directions. After the big thaw that followed, life proliferated, much as it would yet again after the last Ice-Age, when humanity ascended and globally proliferated. Snowball Earth can thus be understood as a vital mechanism for life’s (and later humanity’s) forward evolutionary journey, suggesting what we think of as Arctic is indeed central to the story of life and humanity on Earth – just as “all roads lead to Rome” during Pax Romana two-millennia ago, the Arctic has been a central crossroads and springboard of life for planet Earth.

As today’s Arctic thaws, it can continue to serve in this central role, perhaps more visibly and obviously than in the past. Some scholars see Snowball Earth as more snow, less ice, and thus called a less cryogenic “Slushball Earth.”4)Micheels, Arne and Michael Montenari, “A Snowball Earth Versus a Slushball Earth: Results from Neoproterozoic climate modeling sensitivity experiments,” Geosphere 2008 4 (2): 401–410; Ross, Rachel, “Snowball Earth: When the Blue Planet Went White,” Live Science, February 05, 2019, https://www.livescience.com/64692-snowball-earth.html. Accessed on 17 April 2025. Archaeologists have long known from the ancient fossil record Canada’s Arctic tundra was formerly covered in rich forest during the Paleocene/Eocene boundary, and the few visitors to venture as far north as the Queen Elizabeth Islands in Canada’s High Arctic often come across the petrified forests from this time long ago. As paleobotanist Christopher West has described, “The heady aroma of magnolia blossoms and lotus flowers might have wafted to your nostrils if you had gone for a walk 56 million years ago in the lush green forest which covered Canada’s northernmost islands.”5)University of Saskatchewan, “Canadian tundra formerly covered in rich forest: Ancient plant fossil record shows,” Science Daily, December 12, 2019, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/12/191212163338.htm. Accessed on 17 April 2025. West further notes, “It’s very surprising how similar these ancient polar forests were to some of our modern forests. … The presence of these forests gives us an idea about what could happen over long periods of time if our modern climate continues to warm, and also how forest ecosystems responded to greenhouse climates in the distant past.”

Consider the metaphorical fluidity and centrality of “Arctic” to our world: at one point in time (long ago, in the Cryogenian), our entire planet was a world of ice and snow, not unlike like what Pluto looks like in our outer solar system today, with its famed ice mountains and continent-sized glaciers; while at another point in time (after Snowball Earth underwent its transformative thaw), even the highest of High Arctic territories became veritable “tropical” paradises teaming with life, from dense and fertile forests to productive waters with abundant marine life; and then more recently in prehistory during the LGM, a Eurasian/North America transit corridor opened up between the old and new worlds, globalizing the human story with the peopling of the Americas (whether by land or by sea, or by both). Each of these snapshots from deep-history presents us with different metaphors for the future-Arctic that remain connected to one-another by their facilitation of the life (and later human) journey. A land of perpetual ice and snow, as many had expected the Arctic to remain forever until just a few years ago, was not a barrier to life’s evolutionary advance, but instead a corridor connecting deep-time with our time, and uniting the whole of the world at its top.

From The Ages-of-the-Arctic to the End of Arctic

Looking back to Snowball Earth or the LGM, we gain new insights into our contemporary thaw and its impact upon Arctic geopolitics, which we can understand to be less a break from the past than a return to it; and from the peopling of the Americas during the LGM, we next fast-forward to the contemporary Anthropocene, as the polar-thaw whittles away at our very comprehension of ‘Arctic’ – transforming the region’s distinctive climate and geography. Altogether, these three snapshots spanning nearly a quarter of Earth’s existence help to illuminate and inform our understanding of Arctic geopolitics across the eons. Understanding the interplay of not just human life but life itself on polar ecosystems across this vast stretch of time yields new insights into Arctic geopolitics that are relevant to our own time, reflecting the global and enduring interconnections of the Arctic region to the wider-world.

Each of these periods may be understood as a distinct “Age of the Arctic” – the term coined by Oran Young in 1985 to describe the Arctic geopolitics of the Cold War6)Oran R. Young, “The Age of the Arctic.” Foreign Policy, No. 61 (1985): 160–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148707. – with Snowball Earth being the age when all Earth became a polar icescape, suggesting that “Arctic” is of itself a narrowly conceived era of divergence between both the nonpolar world and the frozen extremes of Earth, and between an unchanging temporal and spatial frozen state, and our current era, the Anthropocene, with its accelerating polar-thaw driven by anthropogenic climate change (what Canadian Arctic expert, author and journalist Ed Struzik foresaw in 1992 as a looming “End of Arctic.”7)Ed Struzik, “The End of Arctic,” Equinox, No. 66: November/December 1992, 76-91.

But in between these poles of divergence, the polar world has in fact ebbed and flowed with a dynamic cycle evident in the geological record, even though the human experience of Arctic is bookended by the frozen world of the ice-age during the LGM, and today’s warming (and sometimes burning) Earth. At various times in this long temporal gulf, the Arctic has served in turn as a geopolitical ‘Rimland’ (the term popularized after World War I, as global naval power was on the rise, by geopolitical theorist Nicholas J. Spykman), ‘Heartland’ (the contending concept popularized by his predecessor, Halford J. Mackinder, in the latter years of the colonial era prior to the cataclysm of World War I) or a remote and isolated ‘Lenaland’ (a lesser-used term also coined by Mackinder) that imagines the Arctic as a frozen and isolated region, as many did before the Anthropocene and its accelerating polar-thaw.

Whether we joyfully welcome the arrival of the “Age of the Arctic” proclaimed by Young or mourn the “End of Arctic” as foreseen by Struzik, it becomes clear that these contending visions of the Arctic span a diverse range of sentiments regarding what we may gain versus what we may lose, much as experienced at the dawn of multicellular life during Snowball Earth, and later at the dawn of human globalization during the LGM. Whether we are at the dawn of a new “Age of the Arctic” or in the first spasms of the “End of Arctic,” we find ourselves in Hegelian dialectic that seems to oscillate across the ages between the two, and this oscillation can be traced all the back to Snowball Earth 720 million years ago, and all the way forth to our present time.

Conclusion

These disparate ages of the Arctic could even apply to our contemporary quest for life beyond Earth, at the interface between ice and liquid water, whether on the icy moons of Jupiter or deep in Pluto’s core, or on exoplanets circling distant stars in those solar systems’ habitable zones. Back here on Earth, if we broaden the time-scale of our discussion of Arctic geopolitics, and consider human prehistory and deeper geological history as part of its story, we could christen this a pendular age of Arctic dynamism that is vast and enduring, extending from deep into Earth’s past to our own time. The immediate relevance of deep-history to the present may not always be obvious, since it not only predates the evolution of humanity, but marks the transition from single-celled life to more complex multicellular life. But as metaphor – to help us understand the range of changes in Arctic climate that we observe across the eons (measured in billions of years) – we come to understand the Arctic as an inherently dynamic place where change in many ways is the norm, and not the exception.

In such a world, Arctic climate change is not an episodic crisis nor an ephemeral event, but rather the status quo for at least the last quarter of our planet’s (and solar system’s) existence. Arctic dynamism embodies a dynamic fluidity and perpetual motion that greatly contrasts with the traditional view of a frozen and unchanging Arctic: whether we look much deeper into the past, to geological history (millions of years ago), or less deeply to human prehistory (thousands of years ago), or even more recently to the colonial era when globalization integrated the global economy (centuries ago), we find some intriguing connections to and parallels with the Arctic of our own time. While contemporary Arctic geopolitics has been deeply impacted by anthropogenic climate change, if we recontextualize man-made effects as only the latest biological disruption to Earth climate system by the world’s current predominant species, human beings, we can more readily understand the connection to the biological renaissance that followed Snowball Earth, and other periods of climate change resulting from disequilibria to Earth’s biosphere by runaway carbon or methane production by one species or another across the ages. The Anthropocene thus becomes more a norm and less a deviation from historical trends across geological time.

In the murky depths of geological and human history, we can both re-contextualize and transition from the contending ages of the Arctic to a broader discussion of Arctic climate (and its dynamic change) reaching deeply back in time, indeed, all the way back to the Cryogenian period, in striking contrast to today’s world, defined since the end of the LGM by a shrinking cryosphere in just our polar regions and in high alpine glaciers like the Himalaya (called by some the “Third Pole”), where what remains of the Arctic is a mere fraction of Earth’s earlier cryosphere, and even when combined with the other cryospheric holdovers (such as terrestrial glaciers in addition to pack ice in the southern ocean) from deep-antiquity, conveys not only an extreme of climate and geography, but its dynamism as well. An increasingly warm and fertile region today amidst the polar-thaw, where plant and animal life that evolved far to its south is now taking root and thriving, it was also at least once before a warm and fertile region. And as a strategic transportation corridor uniting the continents, emergent Arctic sea lanes so widely discussed as part of our future are not unlike the Arctic migration corridors of yesteryear. The Arctic as a dynamic and at times paradoxical state of change, oscillating between its polar extremes while always nudging life (and humanity) further along its road to tomorrow, helps us to understand and contextualize Arctic of today, where change between the extremes of freeze and thaw is of itself the common thread that unites the disparate ages that span almost a billion years of Earth’s story.

Barry Zellen is a Research Scholar in Geography at the University of Connecticut (UConn) and a Senior Fellow (Arctic Security) at the Institute of the North. His 14th book, Arctic Exceptionalism: Cooperation in a Contested World, was published by Lynne Rienner Books in 2024.

Distribution channels: Environment

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release